Alexander Ernest Wilkie 1913-1969

Alexander Ernest Wilkie was born at Calcutta on 7 December 1913. Within a year the First World War had broken out and the families of the soldiers were sent back home. Alex, his older brother Bill and younger sister Mary, were taken back to Glasgow by their mother.

In Glasgow Alex lived with his family in the new east end suburb of Dennistoun, only a few blocks north of the old suburbs of Calton and Bridgeton. Behind their tenement, on Aberfoyle Street, was the expansive Alexandra Park. When he was old enough, Alex went to Whitehill Public School nearby.

Emigration to Australia

On 19 October 1926 Alex's older brother, William, like thousands of others from Scotland, emigrated to Australia under a scheme whereby employers in Australia would sponsor young people from Britain and find them work once they arrived in the country.

Between the time of Federation in 1900 and World War II forty years later, children were seen as ‘ideal immigrants’ . According to the National Archives of Australia, child migrants were

malleable, controllable and adaptable to new conditions. Unlike other migrants, especially during periods of economic recession, they did not invoke the opposition of trade unionists since they were not competitors on the labour market. Child migration was regarded by governments as a form of social welfare, and also as a means of overcoming the decline in the birth-rate (a particular preoccupation of the early years of the twentieth century and of the 1930s) through the introduction of British youth. Governments, British and Australian, both state and Federal, private institutions, philanthropic associations, and the Churches all, from time to time, sponsored child migration. Governments subsidised non-government organisations working in this area between 1921 and 1930 and, in special cases such as the Fairbridge Farm Schools and Dr Barnardo’s Homes, during the 1930s depression years also. Once in Australia, the children were generally brought up to perform manual labour, the girls as domestic servants (referred to in the later part of this period as household workers) and the boys as farm labourers. Children were brought to Australia under a variety of schemes at various ages, some very young.

There were a number of government and non-government schemes that sponsored children to come to Australia. One of these was the Big Brother Movement which sponsored juvenile male migrants, 15–18 years of age.

William Wilkie, aged fifteen and sponsored by the Big Brother Movement, came to Australia on board the Steamship Moreton Bay. The price of the ticket for the third class steerage compartment was ₤33. Three years later, in 1929 Marjory Wilkie, encouraged by favourable reports from her eldest son, decided to take Alex and Mary to Australia.

The Big Brother Movement may sound philanthropic from it’s motto of “Bringing together British Boys and Australian opportunities”. The other motto on the Movement’s newsletter was what would many years later be regarded as unambiguous racism - “Keep Australia White”. However, later readers should perhaps not judge the values of an earlier time with anachronistic moral values but simply accept history as being the way it was and where necessary learn lessons from history.

In Search of a Career

William Wilkie had originally been sponsored to a dairy farm at Maffra in Gippsland, but soon moved to Powling's farm at Framlingham in southwest Victoria.

William Wilkie had originally been sponsored to a dairy farm at Maffra in Gippsland, but soon moved to Powling's farm at Framlingham in southwest Victoria.Marjory, Alex and Mary left Southampton of 22 February 1929 on board the Largs Bay . When they arrived in Victoria they were all able to work on the same farm. Soon afterwards Alex found work on Harry Borbidge's farm “Kurrajong“ near Ararat. He also found work at Hinchcliffe's farm at Tatyoon near Ararat. In 1931, hit by the depression, the Powlings sold their Framlingham property and moved to a farm near Wagga Wagga in New South Wales taking William Wilkie, Mary and Marjory with them.

After a disagreement with the Powlings Marjory Wilkie moved into the town of Wagga where she worked as a cook at a boys' school for several years. Mary, by now a teenager, was attending the Presbyterian Ladies' college at Goulburn, and Alex was working on the farms near Ararat. During the mid 1930s Marjory Wilkie decided to move to Ararat, closer to her younger son. She purchased a house and lived there for many years.

Alex Wilkie gave up farm work and began doing gardening jobs around Ararat, but he felt unhappy with the future prospects that these jobs offered and was always looking for something more rewarding. Perhaps with his father's Black Watch career in mind Alex joined the Ararat based B Company of the 8th Australian Infantry Battalion in 1934 and achieved the rank of Corporal fairly quickly. His dedication and enthusiasm soon impressed people and upon leaving Ararat in 1936 his commanding officer, Captain J.R.Blackman, was more than willing to recommend him to any other Army unit for which he might apply .

Alex realised that he needed to improve his educational qualifications if he was to progress in any career. In Glasgow, he had attended the Haghill Public School in Glasgow until 1925, then the Whitehill Public School where he completed three years before emigrating to Australia. In 1936, he gained a pass in Intermediate Level English from the Austral Coaching College located in the old Rialto Buildings in Melbourne . This was the minimum he would need if he was to enter any profession. He was now twenty three years old.

Home Missionary Work with the Church:

As well as improving his formal education, Alex began playing an active role with the local Presbyterian Church in Ararat. During 1934 and 1935 he assisted the Reverend Samuel Hill at the church as a Lay Preacher. He became enthusiastic about this type of work and applied to the Church to become a Home Missionary. His application was accepted and in October 1936, aged 22, he was appointed as Home Missionary to the isolated hill area between Traralgon and Yarram in South Gippsland.

The people living in the district were mainly small dairy farmers living on isolated properties. A number of families lived in houses attached to the timber mills in the hills. Nearly all the people were poor and had no means of transport.

Alex's task as Home Missionary was to reawaken interest in the Presbyterian Church, and for many, to arouse their interest in any church at all. Upon arriving at Carrajung he toured the district on bicycle, which meant riding on slippery and steep unmade tracks between isolated settlements spaced ten or twelve kilometres apart. It was some forty kilometres from one side of the district to the other. The places he visited included Balook, Blackwarry, Carrajung, Willung, Willung South, Crossover, Calignee and Calignee North. He decided not to continue visiting Calignee and Calignee North as they were about twenty kilometres from the nearest of the other locations and extremely difficult to reach on bicycle.

At each place he posted notices that he intended holding services on the following Sundays. On Sunday 4 November 1936 he conducted his first services: Balook at 11:00 am, then a ten kilometre ride to Blackwarry for a 3:00 p.m. service, and another ten kilometre ride to Carrajung for a 7:00 p.m. service. The response at the first two places was enough to encourage him to continue, but at Carrajung he felt he had had “a complete failure” due to wet weather and the fact that many of the people were Roman Catholics. Nevertheless he persisted and on the following Sundays managed to attract an attendance of twenty five.

Over the next four Sundays Alex managed to visit all of the settlements and conduct services, attracting reasonable attendances at most except Willung South where only four children and two teenage girls attended. Between October and December 1936 he attempted to visit as many of the families living near the settlements as possible. He found that most places consisted of perhaps a hall, store, hotel or school. In most cases the hotel took preference over the school which was often conducted in a public hall. Only one of the settlements had a building used specifically as a church.

One of his tasks was to organise a service at Carrajung to celebrate the centenary of Presbyterianism in Victoria. This service took place on Sunday 26 November 1936 and was conducted by the Reverend Shugg, Director of the Home Mission Department of the Presbyterian Church in Victoria. The Minister spoke of the expanding work of the church throughout Victoria and the need for people to turn to God for support in times of difficulty. About eighty people attended the service, many more than had previously been in attendance. It was acknowledged that Alex Wilkie deserved congratulations for having organised the service and that he deserved the active support of all in his difficult task of serving the people of the bush.

Alex's popularity grew and in the following November he organised a combined picnic at Gormandale for the various congregations of the Blackwarry Presbyterian Mission.

The hill folk turned out in force. It could almost be termed a gathering of the clans, except for the fact that this mission embraces much more than the old Scotch school, because Mr. Wilkie's popularity has created a great deal of undenominational interest in the mission which is serving a district somewhat neglected in the past.

Everyone joined in making the picnic go smoothly, especially the ladies who provided a repast that would tempt the most fastidious, and was a real delight to the juvenile members. Events were well contested, much interest being taken in the inter district relay race which was won by Willung .

In December 1936 Alex submitted a report to the Presbyterian Church outlining his experiences as Home Missionary to the district. He expressed concern over the lack of opportunity for the people to attend a church, and also expressed concern over their poverty which meant that they could barely provide the finances required to maintain a Home Missionary in the district. But Alex's major concern was that he found his own mode of transport almost totally inadequate for the conditions involved. The steep mountain tracks were continually muddy and the constant rain and mist meant that he was soaked through riding from one place to another. He urged the Church to provide him with a more suitable mode of transport that would shelter him from the elements.

The Church eventually agreed to provide him with a car, and, upon the urging of the local people, to allow him to continue for another twelve months in the hope that the congregational attendances would increase and the financial contributions become sufficient to maintain him there on a more permanent basis.

The Church eventually agreed to provide him with a car, and, upon the urging of the local people, to allow him to continue for another twelve months in the hope that the congregational attendances would increase and the financial contributions become sufficient to maintain him there on a more permanent basis.But Alex found that the sheer effort involved in travelling around the district in usually adverse conditions did not allow him enough time to complete the study necessary to become a fully qualified Missionary. At the end of 1937 Alex resigned from the work and returned to Ararat.

Joyce Cosstick

During his time in South Gippsland Alex Wilkie had a girlfriend named Joyce Cosstick. He originally met Joyce through his involvement with the Presbyterian Church in Ararat in the early 1930s. She and her family attended the Methodist Church. They regularly saw each other and enjoyed each other's company. On his move to South Gippsland Joyce, who had been working at the Post Office in Ararat, obtained a position at the Yarram Post Office and boarded with a family of Scottish origins there. She was able to see Alex occasionally as he spent much of his time riding about the damp and misty hills to the north.

During his time in South Gippsland Alex Wilkie had a girlfriend named Joyce Cosstick. He originally met Joyce through his involvement with the Presbyterian Church in Ararat in the early 1930s. She and her family attended the Methodist Church. They regularly saw each other and enjoyed each other's company. On his move to South Gippsland Joyce, who had been working at the Post Office in Ararat, obtained a position at the Yarram Post Office and boarded with a family of Scottish origins there. She was able to see Alex occasionally as he spent much of his time riding about the damp and misty hills to the north. On one occasion they were able to arrange a holiday together and travelled back to Ararat, then to Dimboola for an Oxford Group meeting. On the late night return journey to Ararat the Chevrolet car collided with a truck, driven by Alexander Pappos of Nhill, and overturned. The occupants of the truck were unhurt but those in the car all suffered some injury. Joyce suffered a broken collarbone and spent a short period in hospital before being able to return to work at Yarram.

Working as a Gardener

Alex soon realised that there were limited opportunities in the Ararat and decided to move to Melbourne. In 1938 he was offered work as a gardener in the grounds of Sir Lawrence Hartnett's property Rubra at Mount Eliza. He and a fellow employee, Don Paynter, also from Ararat, were given accommodation in a staff cottage on the property. Joyce remained in Ararat, but regularly took the train to Frankston from where she walked to Mount Eliza to visit Alex.

Alex soon realised that there were limited opportunities in the Ararat and decided to move to Melbourne. In 1938 he was offered work as a gardener in the grounds of Sir Lawrence Hartnett's property Rubra at Mount Eliza. He and a fellow employee, Don Paynter, also from Ararat, were given accommodation in a staff cottage on the property. Joyce remained in Ararat, but regularly took the train to Frankston from where she walked to Mount Eliza to visit Alex.During his time at Hartnett's Alex also worked with the Presbyterian Church at Frankston, where he was on the Board of Management, and with the Young People's Discussion Group at Somerville, soon developing a reputation as a dedicated and enthusiastic leader. His enjoyment in working with people prompted him to take Public Speaking classes run by the Workers' Educational Association of Victoria in 1939 .

Intense disappointment was expressed by church members when Alex decided to leave the district to obtain a position as Gardener at the General Motors Factory at Fishermans Bend. Unfortunately Alex found that the work at the factory was not what he expected and during 1939 and 1940 he applied for several other positions as Gardener, including H.V.McKay Massey Harris Pty. Ltd. at Sunshine, and with the Dandenong Shire Council. He was unsuccessful with these.

Marriage

When Alex moved to Mount Eliza, Joyce Cosstick moved back to Ararat but regularly took the train to visit him. On New Years Eve 1939 Alex and Joyce became engaged and married at the Methodist Church at Ararat in April 1940. Alex's Platoon from the Scottish Regiment formed a guard of honour in full Highland dress and the ceremony was reported in detail in the local Ararat newspaper. After their marriage Alex and Joyce moved to live at Hawthorn while he continued his work with General Motors. Soon afterwards they purchased a four acre property at Springvale South on the rural southeastern fringe of Melbourne. Alex named the property DUNALISTAIR after the Black Watch home in Scotland where he had spent many of his school holidays during the 1920s.

On 15 August 1939 Alex enlisted in the 5th Australian Infantry Battalion, three weeks before Prime Minister, Robert Menzies, announced that Australia was in a state of war with Germany. His Regiment, through careful choice, was the Victorian Scottish Regiment, and his enlistment required him to spend one evening each week at the Barracks and several weekends on camp each year.

With the possibility of war the Australian Government had established the Commonwealth Aircraft Factory at Fisherman’s Bend and General Motors became part of the new Aircraft Production Factory. The Government then drew up a list of Reserved Occupations for implementation in the case of war. Men in these occupations would not be liable for call up. Alex Wilkie's existing connections with General Motors meant that he readily obtained work with the new Aircraft Production Factory in 1941, and despite Australia's war footing he was not liable for full time military service.

War Service

The German invasion of Poland in August 1939 led Britain to declare war on Germany. In making the decision to join the war Australian politicians stressed the ties Australia had with Britain in matters of trade, defence, common ancestry, and the moral justness of supporting Britain in this war. Nevertheless, despite widespread agreement that Australia should make some effort to support Britain, there was disagreement about the extent of that help. Some supported Menzies' view that Australia should give substantial aid to Britain in Europe, while others believed the major effort should be devoted to defending Australia against possible invasion by Japan.

There was clearly some discussion about the matter within the Wilkie family. Alex’s brother, William, enlisted in the Army on 26 June 1940 and embarked for Egypt on 27 December 1940 with the 9th Division .

Japan had declared that it would remain neutral over the question of Germany's invasion of Poland, yet many feared the real intentions of the Japanese. Churchill dismissed any notion of a Japanese invasion of Australia as being extremely unlikely, while the Australian Chiefs of Staff decided to wait for a few months to assess Japanese intentions before sending troops overseas to Europe.

Between 1939 and 1941 Japan had steadily begun to expand into Chinese territory to the north, then into the countries of Indo China to the southwest. Japanese propaganda claimed that the intention was to rid East and South East Asia of the European colonial powers that had supported the region for centuries. In itself this was a fair enough aim. But beyond this the intention was to secure a greatly expanded Japanese Empire, although there was no intention to invade the United States or Australia. Any attacks upon the territory of these countries were part of the short-term tactical strategy.

By October 1941 both Britain and Australia held grave concerns over the British outposts at Hong Kong and Singapore. Britain sent its newest battleship the Prince of Wales, and the destroyer Repulse to Singapore, arriving there on 2 December too late to deter any Japanese advance to the south. By 26 November, unknown to the Australians or Americans, the Japanese fleet sailed for Pearl Harbour. On 7 December 1941 Alex Wilkie turned twenty eight. At 12.30 am on 8 December Japanese troops landed at Kota Baru on the eastern coast of Malaya, and in Thailand. By 4 am they had attacked Singapore, sinking both the Prince of Wales and the Repulse, and had begun their attack on Pearl Harbour. On 12 December they landed in the Philippines. On the sixteenth in North Borneo. By mid December any doubts about Japanese expansion had been dispelled.

By 15 December 1941 Alex Wilkie began full time service with the Australian Army. Within two months another 100,000 men had been called up for full time service.

Military Training

For some time Alex undertook various training programs on the basic soldier's pay of ten shillings per day, paid fortnightly. The allotment system, begun in September 1939, allowed for a certain proportion of the serviceman's pay to be sent home. Out of Alex's ten shillings per day, six shillings and six pence were allotted to be sent home to his wife. There were regular increments in his pay. By June 1942 it had risen to 12/ per day; 12/6 in August 1942; 23/ in April 1944 after being promoted to the rank of Lieutenant; and by May 1945 it had risen to twenty five shillings per day after being sent to Borneo. The amount allotted to be sent home also increased regularly, and there was a system of deferred pay at times when payment was impractical.

Much of the work done between December 1941 and March 1942 was simply referred to as being “in the field”, with the exception of a short period at the Balcome Barracks during mid February. Early in April a week was spent at Mount Martha, followed by several weeks at Melville near Perth, Western Australia. Most of June 1942 was spent “in the field”, probably near Geraldton, in Western Australia. From July 1942 until March 1943 he was at Harvey, about 100 kilometres south of Perth, near Bunbury. Security restrictions forbade any more specific description of his postings, and his record books list the locations using code numbers. Even wives and family were not informed of where the troops were located.

Between 2 December and 26 December 1942 Alex took twenty-four days leave. His first son, Alexander Bruce, had been born on 28 November at Ararat. Alex clearly took the first opportunity to get back home.

Between 13 February and 13 March 1943 Alex attended the Rifle and Bayonet Course at Harvey in Western Australia and achieved the distinction of being the best in the course. Perhaps he had inherited something from his father who had also been one of his regiment’s best shots. He continued his rifle training at the 2nd AIF Snipers School in April 1943 and gained first class results, earning the title of 'Marksman'.

John Hetherington, Correspondent for the Argus visited the jungle warfare training school and filed a report that, although it gives no names, could easily have been describing the training being done by Corporal Alex Wilkie.

I have spent the last 15 minutes balancing tightrope walker fashion, along slippery logs, wading through knee deep pools of slush and wriggling low under rustling branches set across a narrow track.

Flavour was added to the adventure by the knowledge that in any of the slushiest parts a charge might explode and shower me with slimy mud...

It seems hardly the kind of journey a grown man would make voluntarily. But hundreds of grown Australians...are part of the course at this jungle warfare training school deep in the West Australian bush...

A Victorian Corporal headed the party of five riflemen I accompanied over the track. It is called “Little Kokoda”, and is used to train small parties of men in the principles of jungle warfare, as “Big Kokoda”, a nine mile track through the dense bush in which the school is set, is used for training larger bodies of men.

“The idea is to teach the men to move noiselessly, keep their eyes open, and shoot fast and straight,” the Corporal told me, as he handed me a rifle.

You begin to understand the seriousness of the idea right at the start. The way onto the track lies across fallen logs and a slush patch 4 or 5 feet wide.

You are expected to move with a minimum of noise. And that means you must place your feet carefully, let them sink into the ooze, and pretend you like the feel of slime running in over the tops of your boots...

You go along the winding track that is skirted on each side by more or less impenetrable scrub, scrambling over logs, slushing through minor morasses, keeping an eye lifted all the time for the “enemy”.

The enemy here is nothing more dangerous than inanimate targets, pieces of sheet iron cut into the shape and size of men's heads, which peer from behind trees and stumps and clumps of scrub.

But it gives you an idea of how hazardous a journey along a true jungle track could be, how easily enemy soldiers could conceal themselves in heavy tropic growth, and pick off men advancing along a narrow pathway.

Unless, of course, the men advancing along the pathway were sufficiently awake to pick off the enemy lurkers first. And that is one of the principles of jungle warfare that it is this school's business to teach.

The corporal called me to the front of the file, and we pushed on until he touched my arm.

“See that bloke over there!” he whispered. “Let him have it!”

I followed the direction of the pointing finger. Through an opening in the scrub I saw the tin head of an “enemy” soldier a few yards away.

I let him have it, shooting from the hip. Jungle school trainees are taught to shoot from the hip, because in the close pressing jungle there is not often time for orthodox shooting from the shoulder.

The bullet ripped a hole through the target in approximately the position of the left ear. It was one of perhaps 200 holes drilled by the bullets of jungle school trainees who had passed this way.

“You got him alright,” said the corporal, “but you were pretty slow. If he'd been a Jap I think he'd have got you first.”

Which, I fear, was true.

We plodded on, picking off a target here and there, plunging through knee deep bogs. Once there was an explosion, and one of the bogs erupted into a lava of wet, cold, clinging mud. But, happily, I was out of range.

A rifle is an awkward burden in the jungle. You carry it with bayonet fixed and the bayonet has the trick of entangling its point with every branch you pass.

Still, that is part of the purpose of the training learning to carry your rifle so that it doesn't catch on overhead boughs and set them rustling to betray your coming to the enemy.

On such small things do the lives of soldiers in the jungle depend.

I don't know how many tin “Japs” I shot on the journey. Probably a dozen. But, as the corporal said when we reached the end of the “Little Kokoda”:

“You'd have been a dead man more than you killed anybody if it had been the real thing. You have to work fast in the jungle.”

The “Little Kokoda” is only 300 yards long, but its winding bog punctuated route is a test of physical fitness. I came out sweating and panting.

But the men in this school are fit, hard, tough.

They come in here after their normal infantry training for a kind of post graduate course in jungle warfare, and when they leave this school their muscles are tempered into readiness for most of the trials they are likely to meet.

I saw men climbing into and out of pits like agile bears, swarming up and down ropes with monkeylike quickness, balancing across improvised bridges, snaking on their bellies under obstacles only a few inches above ground level.

I saw them laden with 100lb or more of equipment, crossing a river by flying fox, and swimming in winter cold water, pushing laden rafts before them.

And finally I saw them skirmishing their way through a deep timbered gully, part of the “Big Kokoda”. They moved, silent and unseen, through the undergrowth, their presence unbetrayed until they opened up, and the bang of rifles and the snap of breech bolts broke the bush quiet, and set birds screaming for miles around.

Australians might not be born jungle fighters. But in such schools as this they learn fast.

While in Western Australia Alex started up the Victorian Scottish Regiment Fellowship to encourage soldiers of any religious denomination to get together for Christian Fellowship. The Regiments Chaplain reported that the Fellowship's success was largely due to Alex's enthusiasm . In later months the Regiment visited local churches where Alex acted as a visiting elder.

On 8 May 1943 Alex was promoted to the rank of Sergeant, after completing the specialist courses in rifle, bayonet and sniper practice. He was then moved to the Northern Territory. A subsequent move to South Australia in December 1943 where he undertook the OCTU course between January and March 1944. He was promoted to Lieutenant on 2 April 1944. He then took eighteen days leave between 5 April and 25 April.

On 2 May 1944 he was posted to the jungle training school at Canungra, near Surfers Paradise, in Queensland where he remained until November. He was transferred from the 5th AIF to the 2/10th Battalion on 23 October 1944, and moved to Kairi, 40 kilometres inland from Cairns, where he undertook a Flame Throwing course between 19 and 24 April 1945.

The Borneo Campaigns

After three and a half years of intensive training Alex and the 2/10th Battalion were called to serve in Borneo. The mission was to liberate the oil port of Balikpapan from Japanese control. This mission was part of Macarthur's plan to force the Japanese northwards and cut them off from vital supplies. It was one of several campaigns involving Australian forces during 1944 and 1945 that aroused considerable controversy among those who knew they were to take place. Most Australians knew nothing of where their forces were being sent until months after the actions had taken place, and even then the details were sketchy. As it happened, Australia allowed the American General MacArthur to dictate the terms, and MacArthur made use of the available Australian divisions in a series of campaigns of questionable tactical merit. At the time his overall strategy was quite sound although many military advisers believed the Japanese were on the point of surrender anyway.

In Borneo MacArthur planned to set up secure bases from which Java could be liberated and returned to Dutch rule, even though he had often spoken out against colonialism. The Joint Chiefs of Staff vetoed the idea of invading Java but reluctantly approved three landings at strategic places on Borneo Tarakan, Brunei Bay and Balikpapan. These Borneo campaigns were the idea of MacArthur and it was he who had the most enthusiasm for them. His claim was that the capture of Borneo would deprive the Japanese of supplies of oil and provide the allies with fuel. In fact other campaigns to the north and in the Philippines had already cut the Japanese off from Borneo oil supplies and it was more than a year before the allies could make use of them anyway. Nevertheless, MacArthur saw this as an opportunity to give the AIF an active role rather than simply 'mopping up' after the Americans, which had been a legitimate complaint for some time.

The Joint Chiefs of Staff tried to enthuse the British about the plan by claiming that Brunei Bay would be useful to the British Navy. The British were not impressed and said they had no use for Brunei Bay. The landing at Tarakan was intended mainly to provide an airfield to support the landings at Brunei Bay and Balikpapan. The British showed little enthusiasm and the Australian General, Sir Thomas Blamey, believed that the invasion force would be better off moving down the west coast of Borneo towards Singapore, rather than towards Balikpapan. On 16 May 1945 Blamey discussed his objections with Chifley, who in turn suggested to MacArthur that the 7th Division should not be used at Balikpapan. MacArthur replied that it was too late to replace them with an American Division, an argument that Chifley accepted without argument.

Originally it was the 9th Division that was to go to Balikpapan, but on 17 April it was decided that the 7th would go instead. On 7 May the date of the landing was set for 28 June but a preliminary operation at Brunei Bay was delayed so the landing was rescheduled for 10 July. Nine days later it became apparent that the massive build up of troops on the island of Moratai by 19 June would be difficult to sustain so the landing was brought forward to 1 July.

The First Australian Corps, consisting of the 7th and 9th Divisions, embarked from Cairns on 29 May, sailing east and north of New Guinea, recently cleared of Japanese, reaching the island of Moratai, where the Americans had established a base, on 12 June. MacArthur had originally wanted them under the command of the Eight American Army, but Blamey and Prime Minister Curtin objected to being simply subordinates to the Americans. MacArthur agreed that Lt General Sir Leslie Morshead would command the Australian force and would liaise directly, on equal terms, with MacArthur's headquarters.

Borneo was a sparsely populated island, three times the size of the United Kingdom. Japan had been attracted to it because of the oil supplies and its strategic position in relation to Malaya, Java and other islands of the East Indies. It had been easy to capture Tarakan on 11 July 1942 and Balikpapan on 24 January. This brought immediate fear to Australia. By 1943 Japan was making use of the oil supplies from Balikpapan, but within a year this was severely disrupted by raids made by bombers based in Australia. As MacArthur's forces occupied the Philippines Japan could no longer rely upon oil from Borneo. The proposed campaign by the Australian Divisions was therefore questionable from its real strategic value, although many Australians, had they known about the plan, would have supported it because it would give real evidence that the Australians were doing something positive to rid the area of the Japanese invaders. There were also some 30,000 Australian prisoners of war held in camps on Borneo and any campaign on the island which might bring about their release would gain popular support. The public, as usual, did not know about the plans until after the event.

The Borneo campaign began on 1 May with a Brigade of the 9th Division landing at Tarakan and the remainder of the Division landing at Brunei Bay and Labuan Island on 10 June. The largest landing, by the 7th Division, was to take place at Balikpapan on 1 July.

The Australian Press began reporting events linked with this campaign on 17 June, three weeks after the force had sailed, and even the first reports were based on Tokyo Radio announcements that the Allied Task Force had been detected off the coast of South East Borneo headed for the oil port of Balikpapan. There were, according to the Japanese, three battleships, several cruisers, numerous destroyers, and other support ships . The Allied Command did not confirm these reports, but MacArthur issued a communique on 18 June stating that allied planes had bomber gun positions at Balikpapan. On 19 June Tokyo Radio again reported that Admiral Fraser's British Pacific Fleet was sheltering near Balikpapan and that bombers had dropped an estimated 130 tons of bombs on the port. On 21 June a report from Washington stated that allied minesweepers were operating in Balikpapan Bay and Tokyo Radio claimed that these ships were forced to retreat, although it admitted that heavy allied shelling from ships and bombers. Two days later, on 25 June, Tokyo reported 120 Lightnings and Thunderbolts involved in air raids and continued shelling from ships. The Japanese also claimed that they had repulsed an attempted landing by allied forces. The only confirmation from MacArthur's command was that 100 Liberator bombers had raided Balikpapan. Similarly on 26 June, the Japanese reported a landing by Australian troops and continued air and sea bombing. Again, these reports were not confirmed by the allies, although MacArthur did report that 156 bombers of the American 5th and 13th and the RAAF had attacked fuel storages, defence posts, and personnel areas.

Wednesday 27 June 1945 brought more unconfirmed reports from Tokyo. Thirty allied ships, including cruisers and destroyers, were shelling the port and minesweepers were clearing mines. On Thursday 28 June Tokyo gave more precise figures. Three cruisers, 19 destroyers, 14 patrol boats and 9 submarine chasers were operating in the vicinity of Balikpapan. The Japanese reported one cruiser sunk and one damages. By Friday 29 June Tokyo had reported that Balikpapan had been “wrecked” by the continuous bombing and that airfields had been damaged. On Saturday 30 June Tokyo reported that Japanese planes had earlier sunk a Cleveland class cruiser, three other cruisers and one destroyer. It was also reported that the American 7th Fleet had joined the American and Australian forces. On Sunday 1 July Tokyo again reported an allied landing at Balikpapan and reports came in of the town being in flames after the dropping of 2,300 tons of bombs during the previous two weeks. The allied fleet had increased to forty-one ships and a number of transports had also arrived .

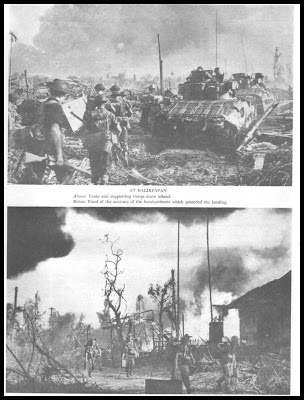

The allied bombing of Balikpapan was carried out in the face of “fantastic Japanese anti aircraft defences consisting of silver balls filled with explosive and suspended from balloons at heights varying from 500ft to 1,800ft”. These defences however failed to prevent the continued heavy bombing of the town .

The Plan for the Invasion of Balikpapan

For some time the Australian Divisions had been preparing for the landing, but it was not until 13 June that the planning units arrived on the island of Moratai. The 2/10th Battalion, under the command of Lieut Colonel Daly, had spent from 12 to 26 June on Moratai doing intensive training and had rehearsed the planned invasion in extreme detail.

For some time the Australian Divisions had been preparing for the landing, but it was not until 13 June that the planning units arrived on the island of Moratai. The 2/10th Battalion, under the command of Lieut Colonel Daly, had spent from 12 to 26 June on Moratai doing intensive training and had rehearsed the planned invasion in extreme detail. Every day thousands of soldiers boarded diesel-driven barges which took them across the bay at Moratai to the three LSI's, HMAS Manoora, Kanimbla and Westralia, or to LST's or to many other types of craft. They practised loading and landing heavy field guns, flame-thrower tanks, Matilda tanks, motor vehicles, and other heavy engineering equipment. On 24 June the convoy steamed up the coast from Morotai to rehearse the amphibious landing. Then, at about midday on 26 June the entire convoy of over two hundred ships carried the Australian invasion force due west for the coast of Borneo.

The 2/10 Battalion was divided into four companies, A, B, C, and D, which were in turn divided into a number of Platoons. Lieutenant Alex Wilkie was officer commanding 12 Platoon, B Company, consisting of thirty two privates he would lead into battle .

The landing was to take place on a 2,000 yard section of beach between Klandasan and Stalkudo. The beach was divided into three sectors Red, Yellow and Green. The 21st Brigade would land one battalion on Green beach, while the 18th Brigade would land the 2/10th Battalion on Red beach and another on Yellow beach.

Red Beach was about one kilometre east of the town of Klandasan, which in turn was about two kilometres south of Balikpapan. The overall objective was to capture, firstly the beach itself, then Hill 87, about 800 metres north of the landing, and finally an area a kilometre to the north west, codenamed Paramatta, which was on high ground overlooking the Balikpapan oil storage tanks.

To achieve this objective Company A was to concentrate on capturing the crossroads codenamed Petersham Junction. These were the main roads leading into Klandasan and Balikpapan. Company B, Alex Wilkie's Company, was to secure the Beach Head and a ridge running north, then capture and consolidate on high ground at map coordinates 585598, about three hundred metres east of Company A's objective at Petersham Junction. Company C was to capture the Paramatta feature several hundred metres further to the north west. Company D was to secure the general area. The overall intention was to move swiftly to the north west and cut off the town .

To achieve this objective Company A was to concentrate on capturing the crossroads codenamed Petersham Junction. These were the main roads leading into Klandasan and Balikpapan. Company B, Alex Wilkie's Company, was to secure the Beach Head and a ridge running north, then capture and consolidate on high ground at map coordinates 585598, about three hundred metres east of Company A's objective at Petersham Junction. Company C was to capture the Paramatta feature several hundred metres further to the north west. Company D was to secure the general area. The overall intention was to move swiftly to the north west and cut off the town .To assist in the visualization of this plan, top secret maps were drawn up showing the relevant features of the area. These were supplemented by aerial photographs taken by daily missions over the area. Anti tank ditches, pillboxes, trenches, bunkers, anti aircraft placements and beach obstacles were all marked, as well as buildings and roads. Three dimensional models were also made of the area to assist in the accurate planning of each step of the mission .

Alex Wilkie's B Company, consisting of three Platoons, was to land on board the landing craft LST632 and were to be accompanied by an MMG Platoon and a detachment of Royal Australian Engineers. The specific intention of B Company's landing was to clear the area south of the Vasey Highway, an area between the road and the beach. It was an area not much more than a hundred metres wide, but containing numerous houses and other buildings, and then proceed to capture the high ground directly north for a distance of some seven or eight hundred metres. The company was responsible for protecting the north flank of the overall operation. During the landing and beach action the LVTs would provide cover for the troops.

The B Company advance was to be carried out in three phases. Phase 1 (a) was the capturing of the beach strip. The Platoons were to be split up, with Platoon 10 going to the right, clearing houses and tunnels in the area to the east as far as Lahey's Bridge. Platoon 11, in the centre, was to clear the area between the beach and Vasey Highway. Platoon 12, to the left, was to deal with the rest of the beach as far as the point where other Company's were operating. The total width of Company B's operation was about one kilometre.

Phase 1 (b) involved sending Platoons 11 and 12 forward along the high ground while Platoon 10 remained in reserve and mopped up after the advance party. Platoon 12 was to send a patrol forward immediately after securing the beach to explore the high ground. This patrol was not to engage in fighting if possible, but was to report on the status of their objective. If all was clear then Platoon 12 would move forward along Spur Road west of the valley, while Platoon 11 would occupy each position vacated by 12. Platoon 10 would then follow Platoon 11 and this movement would continue until the objective was reached. Upon completion of Phase One Private Croker, of Platoon 12, was to report to Battalion Headquarters, which, by then, would have been established on the beach.

The detachment of Engineers was divided up, with one engineer being allotted to each Platoon and one to Company Headquarters. Their role was to move forward searching for mines and booby traps. They were to return to their own units once the operation was completed. It was anticipated that the whole operation would take no more than fifteen minutes after the initial landing at 0900 hours on 1 July.

In the event of Japanese aircraft attack, offensive action would be taken against the aircraft, but the operation was not to cease except in areas directly attacked by aircraft, and even then only if ordered to do so by the Platoon Commander or some higher Command. Alex Wilkie, as Commander of Platoon 12, would be expected to make such a decision in the event of aircraft attack.

Before the operation began each man was issued with emergency rations, a tin of solid fuel, a sterilizing outfit, 100 rounds of 303 ammunition, and two hand grenades. A Comprehensive kit of clothing and personal equipment was packed into haversacks and waterproof rolls. Much of this equipment was to be left on the LVTs and would be unloaded after the operation had begun.

Alex Wilkie, as Commanding Officer of Platoon 12, was required to give precise instructions to each soldier before the operation regarding all possible eventualities. For example, after each phase of the operation expended ammunition had to be replaced immediately. The Platoon would have supplies of PITA bombs and two inch mortars as well as Bren Guns and Owen Sub Machine guns. In the event of injury all would be treated by Medical Officers attached to each Company, and the seriously wounded would be carried, if possible, back to the beach assembly point. Great care was to be taken with water containers. All water was to be superchlorinated for one hour, or boiled, before use. Water bottles were to be filled before leaving the ship. Because of the risk of disease buildings were not to be occupied by troops until cleared by the Medical Officer. Rats were likely to be a problem and rat poison was readily available. Dead rats were to be burned without handling. Relationships with the native population were important and troops were instructed not to molest civilians, enter property without permission, not obtain foodstuffs without the owner's consent or without payment. Food, clothing, or other goods were not to be bartered. Native customs and women were to be shown respect and generally dealings with the population had to be friendly, but not familiar.

When Company B had successfully gained the high ground at 585598 Private Francis was to report back to Major Trevinan at the Beach Assembly Area and the MMG party were also to report back to guide the heavy guns forward. Company B was then to move to Phase Two of the operation, which involved supporting Company A's attack on Petersham Junction crossroads and to protect the right flank of Company A's operation neutralizing any fire from the north and north west. The third phase of the operation was to neutralize enemy positions north of the Prudent area and to be ready to take over from Company A when needed.

This was the initial plan for the Australian Landing at Balikpapan, as written up in Alex Wilkie's notebooks. The time had been set for 0900 hours on Sunday 1 July 1945.

The Landing at Balikpapan

The 18th Brigade had spent 19 days travelling from Queensland to Moratai on the L.S.T's. Each carried 500 troops, which was comfortable for a short voyage, but most uncomfortable on such an extended voyage. After only a short period ashore on Moratai they embarked again for the five day voyage to Balikpapan. The official 18th Australian Infantry Brigade Report on Operation Oboe Two stated that there was insufficient time at Moratai for the troops to regain their fitness and become used to the climate, and not enough time for adequate briefing about the operation. Luckily the weather at Balikpapan on 1 July was cool and so the men were not unduly hampered by the climate .

The convoy of 100 ships sailed from Moratai at 1:30 p.m. on 26 June, passing north of Halmahera and Celebes and then south along the Strait of Macassar. On the morning of the 29th the warship group passed the transports and the ships arrived at a point eight miles south east of the landing site an hour and a half before sunrise.

Two hours before the landing, at 7:00 am, the five cruisers and fourteen destroyers stationed off shore began a terrific concentrated bombardment of Japanese defences. For days American and Australian warships had been shelling the area because of the extent of Japanese fortifications, which included land and sea mine fields, timbered defences along the beaches, gun placements, anti aircraft batteries, tunnels, caves, pillboxes, trenches and airstrips. With such potential opposition it was essential that the Japanese were weakened as much as possible before the actual landing occurred. The massive bombardment of Balikpapan was the biggest Australian artillery effort of the war. On the landing day alone 1,605 six pounder shells were fired, 1,425 high explosive mortars, and 137 phosphorus bombs. The Naval bombardment that day included 250 eight inch shells, 3,000 six inch shells, 6,000 five inch shells and 8,800 rockets. During the weeks to 17 July 1945 a total of 47,500 shells and 8,800 rockets had been fired at Balikpapan .

The first and second waves of troops were carried in nine L.S.T's to a line some 3,000 yards off shore. From there some 51 L.V.T's were launched and took the 18th Brigade to the beach.

The 2/12th Battalion was meant to land on Yellow Beach and then head north, but it was landed with the 2/10th on Red Beach. The 2/27th and the 2/14th were supposed to have landed on Green Beach, but were landed on Yellow by mistake. After some confusion with the various companies attacking positions not originally intended as their targets the troops ended up in the right places .

The 2/10th was landed in the right place, on Red Breach, and had the crucial task of taking the Paramatta ridge which gave access and domination over the town itself. At 8:55 am, the first two Companies ashore, B and D, had to secure the high ground overlooking the beach and seal off the left flank. A few minutes later, at 9:08 am, the second two Companies, A and C, came ashore about 800 yards west of the intended place. This caused some delay in bringing the mortar and machine gun platoons into action.

In the meantime Companies B and D moved rapidly to their objectives, securing the area between Vasey Highway and the beach, and the sent patrols on to Petersham Junction and Prudent, both of which were found to be unoccupied. Their findings were reported back to the beach as planned.

Company A, commanded by Captain R.W.Sanderson, headed for Petersham Junction under some small arms fire. Lieutenant A. Sullivan's Platoon secured the lower slopes of Hill 87 in order to provide cover for Petersham Junction where Lieut Colonel Daly was establishing his command post.

The cruiser U.S.S.Cleveland was meant to be supplying heavy fire support for the assault on Hill 87, but was called to other duties. Daly had to decide whether to wait for another ship, and risk the Japanese regrouping, or to attack immediately without cover. He decided to attack immediately.

At 10:10 am Company C, under Major F.W.Cook headed for Hill 87. The three Platoons of the Company, 13, 14 and 15, came under sustained fire from the higher ground on Paramatta and lost several killed and wounded. Platoon 15 lost 13 killed by the time it reached Hill 87. By 11:40 am two tanks had arrived and enabled the Hill to be captured by 12:50 am.

At 10:40 am the 2/9th Battalion which had been held in reserve on the beach was ordered to relieve Company B of the 2/10th near Prudent. This company then moved to join the remainder of the 2/10th at Petersham Junction.

Company A under Major Sanderson was then ordered to relieve Company C on Hill 87. Company C would then move on to take Paramatta. By 2:12 p.m. Paramatta had been taken and from there the attack on the town could begin.

At 4:55 p.m. the Americans decided to lend a hand and dropped bombs and rockets onto Hill 87, which had been in the hands of the 2/10th Battalion for over four hours. As a result three Australians were killed and fourteen wounded.

Within three days the 2/10th had captured the town of Balikpapan, having lost 16 killed and 40 wounded, and having buried 332 Japanese .

The Reporting of the Balikpapan Landing

In Australia, Joyce Wilkie, knew only what she could read in the newspapers about the operations at Balikpapan.

Rupert Charlett, the Argus reporter at Balikpapan described the landing:

Balikpapan was another Gallipoli, but this time we stormed the enemy defences with high explosives instead of men with rifles

On Tuesday 3 July the Argus reported the landing:

Veterans of Australia's 7th Division who stormed ashore at Balikpapan, Borneo, on Sunday have made swift progress. The Japanese are falling back into the jungle.

Although fanatical resistance has been encountered in some sectors, the Japanese are believed to be fighting a desperate delaying action to cover a general retreat northward.

One Australian force is striking westward from the beachhead, two miles SE of Balikpapan, to cut off the town.

The success of the Australian invasion was apparent within two hours of the landing. By late Sunday afternoon all of the day's objectives had been achieved with the Australian troops having advanced up to a kilometre and a half to the west and east from the beachhead. The Argus reported other elements of the landing:

The biggest and finest equipped Australian amphibious force yet to go into action went ashore at Klandasan, the European quarter of Balikpapan, and quickly won a 2,000 yard beachhead.

The Japanese had been blasted from the beach area by one of the most terrific naval, air and rocket bombardments ever provided for a SW Pacific operation.

A Japanese shore gun opened fire on one of the destroyers but its four shells went wide. They were the only shells it fired, as dive bombers obtained direct hits on it before the gunners could reload.

A lone Japanese AA gun fired on the landing barges, but Beaufort bombers promptly dived on the gun and obliterated it after it had fired only a dozen rounds. Not a Japanese plane was to be seen.

The Japanese, with most of their heavier weapons destroyed, could only fight doggedly as they were wiped out foxhole by foxhole.

When war correspondents came ashore 28 minutes after the first landing they found a bewildering scene of devastation. Buildings and Japanese concrete pillboxes were heaps of rubble .

Within minutes of the landing, engineers had marked safe passages for the unloading of tanks, jeeps and bulldozers. The first Japanese defences were encountered on the high ground to the west of the landing, only about two hundred metres from the beach. They were quickly dealt with by tanks and mortar teams, together with tank and manual flamethrowers.

Heavy resistance was also encountered to the east along the Klandasan River when the Australians suffered some casualties from machine gun fire .

Despite three years of intensive training the task facing Alex Wilkie and his men must have seemed frightening, not only because of the extent and desperation of the Japanese defence, but also because of the ferocity of the allied bombardment of the beach area beforehand. Yet the landing was described by Rear Admiral Albert Noble as being “an outstanding success, reflecting the great courage and high standard of efficiency of all forces engaged” .

Perhaps one of the motivations which overcame any fear is to be found in the lines of the Army's official handbook for officers: By every trick, device and cunning...remember that your be all and end all is to KILL JAPS!

With this aim in mind it might be expected that reports in the Australian press at the time would emphasize the successes of the campaign and give little emphasis to Australian losses. Reports of Japanese resistance and Australian casualties tended to be played down, but the impression is that the fighting was ferocious and it was openly acknowledged that Japanese defences were “the strongest encountered for a long time” . It was later reported that:

The general opinion is that the Balikpapan garrison is comprised of picked enemy troops. Many are considerably above the stature of the normal Japanese, and personal equipment is superior to that of the average Japanese infantryman.

By Monday 2 July the invasion force had extended their drive to over two kilometres inland and were heading both east, towards the Sepinggan airfield, and north west into the town of Balikpapan itself. Japanese gun placements east of the town, about three kilometres from the beach, hindered the advance and allied naval guns and artillery saturated the area with shells.

Rupert Charlett, the Argus correspondent who accompanied the landing, reported that:

The Japanese had elaborate defence positions in depth beyond the beaches, including deep tunnels, some 50ft long, heavily protected concrete pillboxes, and well camouflaged sniper posts. Sniper fire throughout the day was heavy. Enemy machine gun crews fought to the last man, but despite their well planned defences our superior fire power, particularly artillery, and our aerial support, exacted a heavy toll.

One pillbox pinned the Australian infantry down with accurate machine gun fire, and a tank was called in. Creeping behind it with some infantrymen, I witnessed a point blank battle between tank and pillbox. High explosive shells ripped through the concrete and there was a terrific explosion inside the pillbox. One Japanese catapulted 20ft into the air like a rocket.

To the north of Balikpapan dense tropical jungle penetrable only along narrow tracks, will probably be the scene of bitter warfare against an enemy, which reconnaissance has shown, has prepared for a fighting retreat.

Within two days the Australian forces had extended their bridgehead to five kilometres and had driven over three kilometres inland. The Companies of 2/10 Battalion had made the greatest and most spectacular advance and had achieved their objective of capturing the Paramatta Hill overlooking Balikpapan. And yet it was in the area of this advance that the greatest Japanese opposition had been encountered. The victory was reported by the Argus to have been at the cost of three hundred Japanese killed. The paper made no mention of Australian casualties but on 6 July Tokyo Radio claimed that 1,100 allied troops had been lost since the landing, including 700 at sea. A significant Australian War Cemetery was established at Balikpapan within a few weeks.

The next step, after securing Paramatta Hill, was to invade the town itself. Alex Wilkie's Battalion, the South Australian based 2/10th, had come down from the high land above the town and was driving towards the centre of the industrial area west of Paramatta within two days of the landing .

By Friday 6 July it was reported that the AIF had occupied most of Balikpapan, two days ahead of schedule. All of the oil refinery buildings had been destroyed by bombing, and the waterfront had been devastated. By Saturday the entire town had been occupied and a number of new advances were started inland.

When the Commander in Chief of the Australian Military Forces, General Sir Thomas Blamey, visited Balikpapan some weeks later, he visited the Paramatta Hill area and summed up the campaign:

The Balikpapan campaign has been extraordinary. We have never before tackled beachheads so heavily defended. The Japs had scores of dual purpose guns, but we got right in on the heels of the pre landing bombardment and our tactics in the vital opening stages were often brilliant. The 2/10th Battalion, for instance, took the vital key features on the first day. That was a first rate performance.

Within four weeks of the occupation of Balikpapan the Japanese had surrendered. By 2 September the war was over. It is now known that they were seriously considering surrender probably before the Borneo Campaign. the dropping of the American atomic bombs on Japan was said to have hastened the surrender, but was probably not the deciding factor. The question remains as to whether the Borneo campaigns were really necessary to weaken the Japanese if they had virtually given up anyway.

Alex Wilkie remained in Borneo until 29 December, four months after the war had officially ended, and returned to Australia on 11 January 1946. He was discharged from the army at the Royal Park Barracks in Melbourne on 30 January 1946 and on 31 January was transferred to the Reserve of Officers .

Post War Retraining

Early in 1946 Alex applied for training with the Commonwealth Reconstruction Training Scheme (CRTS). His application was granted by the Ministry of Post War Reconstruction in March. He was to commence a refresher course in Horticulture at Burnley Horticultural College on 8 October 1946 . The course finished on 7 April 1947.

On 10 April the Principal of Burnley, T.H.Kneen wrote to Alex:

I was so impressed by the plan you submitted to Mrs. Gibson for the landscaping of the new school building, as part of your final examinations, that I am prompted to ask if you would do us the honour of presenting your design to the school.

Not only would this form a unique record of your training here, but I am quite certain that many of the features you proposed would find their way into the final plan.

This was certainly an encouraging start to his post war career. Alex Wilkie's early experiences on the farms and as gardener at Ararat, his experiences in the mountain forests of South Gippsland, and his work as gardener at Sir Lawrence Hartnett's at Mount Eliza and at General Motors had aroused in him a love for the environment and a desire to protect it. He looked for work in these areas.

Save the Forests Campaign

After the 1939 bushfires in Victoria a number of people had become aware of the need to protect the forests of Victoria. One of these was Cyril Isaac, MP for South Eastern Province, who drew up a plan for a Save the Forests Campaign in 1944. Using trees donated by the Forests Commission, Isaac organised the planting of 105,000 trees in community forest programs across Victoria during 1945 and 1946 .

In 1946 while completing his Burnley course, Alex had worked casually at Isaac's nursery at Dandenong . By 1947, on completion of his Burnley course, Alex Wilkie had joined the Campaign as its Field Officer. One of his first major duties was to take part in a Field Day at Charlton in North Western Victoria. Six hundred local people turned out to plant a forest of some 1500 trees . This event was to become the model for similar events which took place all over the state. As Field Officer, Alex was responsible for demonstrating the techniques of tree planting, educational programs, and publicity for the Campaign .

By the end of 1949 Alex had supervised the planting of 142 demonstration plantations, some 22,000 trees, across the states Soldier Settlement blocks. By 1 December 1949 the Warrnambool Standard reported that the “Save the Forests Campaign is a superb example of the unofficial initiative that has support and representation from the government”. The emphasis was upon community support.

By the end of the 1940s there was a need to rethink the direction of the Campaign as it had grown beyond its original aim of saving the state's forests and had become concerned with the major conservation issues of forests, soil and water. The demand for trees for planting had become so great that in 1947 Alex Wilkie had offered the Campaign the use of his own 4 acre property at Springvale South to establish a nursery. The offer was immediately accepted and the nursery established with Alex being appointed Manager of the nursery .

By the end of the 1940s there was a need to rethink the direction of the Campaign as it had grown beyond its original aim of saving the state's forests and had become concerned with the major conservation issues of forests, soil and water. The demand for trees for planting had become so great that in 1947 Alex Wilkie had offered the Campaign the use of his own 4 acre property at Springvale South to establish a nursery. The offer was immediately accepted and the nursery established with Alex being appointed Manager of the nursery .The establishment of the nursery was essential not only for the supply of trees, but also to provide research, education and publicity. By 1951 the nursery had 100,000 trees in stock without any capital outlay on the part of the Campaign .

The success of this “temporary” nursery was sufficiently remarkable to warrant a formal visit by state parliamentarians in 1949. They were impressed and approved a major increase in government grants to the Campaign for the following year.

Natural Resources Conservation League

Alex' initiative continued when he noticed a substantial area of land for sale opposite his own property on Springvale Road. He immediately used his own money to make a down payment and suggested to the Campaign Committee that the land should be purchased as a permanent nursery. This was subsequently done and the Campaign Headquarters was moved from Melbourne to the new site at Springvale with a new name of Natural Resources Conservation League. The nursery was moved to the new site and Alex Wilkie appointed Manager of the NRCL Nursery.

As well as running the daily operations of the new nursery, Alex retained his role as Field Officer and Publicity Officer and set an example of loyalty to the work which was emulated by most of the staff who became involved with the League . Cyril Isaac had made a personal promise to Alex that he would be promoted to the position of Director of the League upon his own retirement. Later this promise was not forthcoming and in 1958 after a serious disagreement about his future role with the League, Alex resigned much to the dismay of all who had worked with him.

Treeplanters Nursery

In 1959 Alex Wilkie established his own nursery on his own land at Springvale South. Building on his experience with the NRCL he had printed brochures to assist customers with treeplanting and took a personal interest in the treeplanting problems of many customers. the nursery became known at the Treeplanters' Nursery and achieved a reputation during the 1960s for being a place specialising in Australian native plants and offering personalized service . Alex also achieved a small degree of fame at that time through his regular appearances on the ABC Television program Town and Country which featured a gardening and horticultural segment. He was already well known across rural Victoria through his field work with the Natural Resources Conservation League.

Superintendent of Parks and Gardens - City of Springvale

In 1961 Alex applied for the newly created position of Superintendent of parks and Gardens with the City of Springvale and was subsequently appointed to the job. The nursery, now known as Treeplanters' Nursery was left to his wife and son, Bruce, to manage.

As Superintendent of Parks and Gardens Alex was responsible for the planning, planting, construction and maintenance of the city's parks and gardens. Little had been done previously and he embarked upon a program which would transform many areas of the municipality. At the same time he entered a more professional life becoming a founding member, and later President, of the Rotary Club of Springvale and member of the Australian Institute of Parks and Recreation (AIPR). His interest in promoting the good design of parks and gardens meant that he soon became founding Editor of the Institute's journal Australian Parks and was made a Fellow of the Institute.

During the late 1960s the Springvale City Council wanted to develop several acres of bushland in Springvale South. Alex recognized this as being the last remaining area of original bushland in the district and proposed that the area should be set aside as a reserve. He then began the painstaking process of identifying and cataloguing every species of plant growing in the reserve. He did not finish the task, but after his death the Council continued with his plan and named the area the Alex Wilkie Nature Reserve.

Alex Wilkie suffered a stroke in 1967 and died of heart attack in 1969. His career from the time of his arrival in Australia in the late 1920s had been one of concern for community service and for the environment.

Footnotes

Full documentary referencing of sources is available for this information. Contact me for details.

1 comment:

What about older brother William John Wilkie, is there any more information on him?

Post a Comment