For King, Country and Empire

Alexander James Gilmour Wilkie was the seventh and youngest son of William Wilkie the Second. He was born at 101 Greenhead Street, Calton, at ten-thirty on the morning of 30 May 1882 and baptised at Saint James’ Church by the Minister, John Henderson, on 11 July 1882 .

Alexander James Gilmour Wilkie was the seventh and youngest son of William Wilkie the Second. He was born at 101 Greenhead Street, Calton, at ten-thirty on the morning of 30 May 1882 and baptised at Saint James’ Church by the Minister, John Henderson, on 11 July 1882 .When he was old enough Alexander went to the John Street Public School in John Street, Bridgeton. This school had opened in 1883 and by 1900 was very well equipped with science laboratories science teaching being one of its primary purposes. The Principal, Robert Paterson, was accredited with the high standing of the school during these years .

After he left school Alexander took a position as a clerk, but on 23 August 1900, aged eighteen years and two months, he decided to enlist for seven years service with the Royal Highlanders at Glasgow. This was to be followed by another five years in the reserve . His enlistment papers indicate that he was five feet three and a half inches tall, had a pale complexion, blue eyes and fair hair. After enlisting Alexander continued his education and received certificates for the 3rd, 2nd, and 1st classes during 1900 and1905, and a pass in composition in 1908 .

The 2nd Battalion of the Royal Highlanders Regiment, commonly known as the Black Watch, was one of the most famous of Scottish Regiments and had regularly visited Glasgow. Alexander undoubtedly saw them on parade and heard of their legendary campaigns. Between 1869 and 1874 the 2nd Battalion had been in Ceylon. After a move to Lucknow it moved back to England in 1881. In 1883 they moved to Aldershot, in 1886 to Dublin, then to Belfast. In 1893 the Black Watch moved to Glasgow for a short period. Alexander Wilkie would have been eleven years of age and most certainly saw the Battalion during that visit. After Glasgow the Battalion moved to Edinburgh, then in 1896 to York, and in 1898 to Aldershot.

Why did Alexander decide to join the army, rather than go into the family business? The business had been taken over by his older brothers, William III, who was some nineteen years his senior, and Conal Alexander was virtually a generation younger. The reasons may never be known, but it is, of course, common for sons to enter very different occupations to their fathers, just as it was common for sons to follow in their father's footsteps.

Why did Alexander decide to join the army, rather than go into the family business? The business had been taken over by his older brothers, William III, who was some nineteen years his senior, and Conal Alexander was virtually a generation younger. The reasons may never be known, but it is, of course, common for sons to enter very different occupations to their fathers, just as it was common for sons to follow in their father's footsteps.The Boer War took the Battalion to South Africa in 1902, however Alexander was at Aldershot undertaking Gymnastics training during this time . On 1 July 1902 he was awarded a certificate qualifying him to act as Assistant Instructor in Physical Training under the supervision of a staff instructor . By 23 August 1902 he was granted good conduct pay and a medal .

On 27 October 1902 the Regiment, with Alexander Wilkie, embarked for India, arriving there on 21 November . In 1903, when the Battalion was in Umballa, near the North Western Frontier, he was already a Corporal, and had been enrolled in a Marksman’s class, training he continued throughout 1904 and 1905 . He also continued his Gymnastics and Physical Training classes at Umballa during the same years. At a Regimental Concert held in Solon on Saturday 22 August 1903 Lance Corporal Wilkie presented an acrobatic performance with Privates Bird and Fotheringham, and a display in fencing with Corporal McKenzie . Another Regimental Concert was held on Saturday 5 September 1903 and at a concert of the Black Watch Variety Club held at Umballa on Wednesday 29 June 1904 Lance Corporal Wilkie was the accompanying pianist for the other performers as well as performing gymnastics and acrobatics .

During 1904 Alexander Wilkie undertook further courses in Gymnastics and Swordmanship and on 25 March was issued a certificate allowing him to act as a full instructor of both disciplines. He achieved first class proficiency in both .

The next move was to Peshawar, close to the Afghan border, in 1906, and it was here that Alexander was promoted to the rank of Corporal Sergeant on 10 February 1906. He also undertook a special swimming course, achieving his certificate on 8 May 1906.

The Regiment remained at Peshawar until 1907 .

The North West Frontier:

Lord Curzon, the Viceroy of India created the North-West Frontier Province in 1901, in an attempt to give the region an identity separated from the administration of the Punjab. The problem was basically that the Muslim tribes of the north west mountain regions did not get along with the Hindu people of the more settled plains of the Punjab. The intention was to enable the tribes to govern themselves while tribal militias, commanded by British officers, would help to keep the peace .

In 1893 the Durand Line had been drawn up and Wazirstan came under British rule. Earlier the British had been able to exercise some semblance of control over Baluchistan with the co operation of the Baluchi chiefs. It was assumed that the Wazir and the Mahsud tribes would enter a similar agreement. But the tribal chiefs refused to comply and a campaign of murder and terrorism followed.

By 1897 the British decided to mount a brutal punitive expedition led by Sir William Lockhart. Rather than subduing the tribes, the Mahsuds looked to their leader Mullah Powinda to seek revenge and a protracted campaign of harassment began. There was little that the people of the towns could do. Indian law prohibited them from arming themselves and the Mahsud raids were generally so swift that they were gone before the local militia could respond. To add to the problem, the British Officers commanding the militia could never really be sure that the militiamen, many of whom were related to the Mahsuds, would respond anyway .

By 1900, after refusing to pay a ten thousand pound fine, the Mahsuds were placed under military blockade. This did not succeed so a punitive expedition lasting four months was mounted. The fine was eventually paid in March 1902 . For the next two years Mullah Powinda appeared to have reformed, but by 1904 bombing raids began again with members of the local militia carrying out Powinda's assassination missions. This continued until 1908 when the British ordered more military reprisals.

In the meantime, in 1907 Britain and Russia had signed an agreement in which they decided to keep Afghanistan as a buffer state with Britain controlling Afghan foreign affairs while agreeing not to annex the country. The Afghan leader, Habibulla, had a fairly friendly disposition towards the British and had visited Peshawar in 1904 and Simla in 1907. However other factions in Afghanistan were fiercely anti British and actively supported the Muslim rebels of the Northwest Frontier .

In the Khyber Pass area west of Peshawar, the first ten years of the 20th century became known as a period of “weekend wars” because of the seemingly endless terrorist missions carried out by the Muslim tribes people.

In 1898 the Afridi people, with the exception of one clan, had agreed to a cease-fire with the British. But the Zakka Khel clan refused, believing that continued turmoil would prompt British reprisals and spur the other clans to rejoin the rebellion .

The Zakka Khel were led by the hypnotic Khawas Khan who eventually, in 1907, declared unilateral independence from the region. To get the point across he sent raiders into Peshawar in an attempt to kidnap the Assistant British Commissioner. Alexander Wilkie was stationed at Peshawar at this time and had achieved the distinction of being one of the Battalion's “best shots”. It was certainly a skill that would be useful in Peshawar in 1907.

In 1908 eighty clansmen in stolen police uniforms staged raids in Peshawar. Local outcry led the British to react before other Afridi tribes were encouraged to join the rebellion. Within two weeks the Indian army under Major General Sir James Willcocks attacked that Bazar Valley, south of Peshawar, and inflicted high casualties on the Zakka Khel people. By March 1908 the clan had agreed to refrain from further rebellion, although opposition to British rule continued.

In 1908 the Black Watch Regiment moved to Sialkot some three hundred kilometres to the south east of Peshawar. Perhaps three years in the Northwest Frontier were enough. Many of the photographic records extant of Alexander's activities at this time show him engaged in gymnastics activities and it seems apparent that this was perhaps his major liking as a member of the Battalion.

Later in 1908 Alexander Wilkie returned to Edinburgh for a brief period and on 2 January 1909 married Marjory Isobel McCombie . The wedding took place at Marjory’s home at 13 Lower Granton Road, Leith. Witnesses to the marriage were Alexander’s sister, Janet Glen Wilkie, and brother William. Marjory’s mother, Elizabeth, was also present .

Alexander and Marjory returned to India soon afterwards and were stationed at Karachi on the coast of present-day Pakistan, on the Arabian Sea . The Battalion Camp at Karachi was a desolate and dusty place brightened only by the rows of white canvas tents shining in the sunlight.

While at Sialkot Marjory gave birth to a daughter who was named Elizabeth Jane. She was born on 30 September and baptized on 19 December 1909. Unfortunately Elizabeth died just over a year later and was buried at Sialkot . Alexander and Marjory commissioned M. Imtiazaly and Company, Sculptors of Sialkot, to make a substantial marble monument for their child’s grave. The monument was ready by 17 February 1911 and cost seventy-nine rupees .

During the next few years Alexander and Marjory Wilkie were stationed at Peshawar, Sialkot and Solon. Peshawar is some thousand kilometres to the north of Karachi on the Afghan border; Sialkot some three hundred kilometres south east of Peshawar; and Solon about the same distance further southeast. It is apparent that the Battalion moved about the country at regular intervals.

During the next few years Alexander and Marjory Wilkie were stationed at Peshawar, Sialkot and Solon. Peshawar is some thousand kilometres to the north of Karachi on the Afghan border; Sialkot some three hundred kilometres south east of Peshawar; and Solon about the same distance further southeast. It is apparent that the Battalion moved about the country at regular intervals.On 25 February 1911 Alexander was promoted to the rank of Sergeant . Also in 1911 he requalified as an Instructor in Physical Training . On 29 April 1911 Alexander and Marjory’s first son was born at Ambala. He was named William John and baptized at Barian in the Muree Hills .

Coronation of the King Emperor:

In December 1911 Alexander Wilkie was with the Battalion when it was selected, with the Gordon Highlanders, to take part in the Coronation Durbar held at Delhi for King George's coronation as King Emperor of India. The Battalion, consisting of 21 Officers, 2 Warrant Officers, 41 Sergeants and 740 rank and file soldiers, left Sialkot on 23 November 1911 and joined 54,000 other troops assembled at Delhi on the following day. On 7 December 1911 the Battalion took part in the State Entry of King George V into Delhi.

In December 1911 Alexander Wilkie was with the Battalion when it was selected, with the Gordon Highlanders, to take part in the Coronation Durbar held at Delhi for King George's coronation as King Emperor of India. The Battalion, consisting of 21 Officers, 2 Warrant Officers, 41 Sergeants and 740 rank and file soldiers, left Sialkot on 23 November 1911 and joined 54,000 other troops assembled at Delhi on the following day. On 7 December 1911 the Battalion took part in the State Entry of King George V into Delhi.On 11 December the King presented the Regiment with new colours and made an address in which he recalled with pride the deeds of those who had been members of the Regiment in earlier times. The King's address provides some insight into the attitudes held by the soldiers, and therefore, probably, of Alexander Wilkie, towards the role of the soldier and the role of Britain in India and the world.

In presenting the new colours the King observed that the flag was no ordinary flag but a “Sacred Ensign”. It was, by inspiration if not by actual presence, “a rallying point in battle”. It was “the emblem of duty; the outward sign of your allegiance to God, your Sovereign, and Country: to be looked up to, to be venerated, and to be passed down untarnished to succeeding generations”.

The king then made reference to the Regiment's bravery and loyalty: “should such a sacrifice as that of 1815 be again required of you, I feel sure that, even though more than half of your numbers should fall in a single action, the remnant will stand firm as they did at Waterloo”. This reference was to a battle which took place on 18 June 1815 when the Battalion repulsed eleven French Cavalry charges, but lost 289 of its 498 men. If such was the loyalty and devotion of the men in the Battalion in 1911 then the events that were to follow in the next few years can more clearly be understood.

On 12 December 1911 the Black Watch formed a Guard of Honour for the Crowning of the new Emperor of India. The King was so impressed that he ordered each member to be given a special Coronation Medal.

In January 1912 the Battalion followed the King and Queen to Calcutta where they took part in all the ceremonies in connection with the Royal visit to that city . On 28 September 1912 the Officers and Sergeants of the 2nd Battalion took part in a dinner at Fort William, Calcutta, in honour of His Imperial Majesty King George V having become Colonel-in-Chief of the Regiment .

Alexander and Marjory’s second son, Alexander Ernest, was born during the posting to Calcutta, on 7 December 1913.

In 1914 the war was declared against Germany. Marjory, William and young Alex were evacuated back to Britain. They found a residence at 38 Aberfoyle Street, Dennistoun, in Glasgow.

On the outbreak of the war there were seven Black Watch battalions. In addition to the Regular 1st and 2nd Battalions and 3rd (Special Reserve) Battalion there were a further four territorial batallions which had become part of the Regiment in 1908. They were the 4th Dundee, 5th Angus, 6th Perthshire and the 7th from Fife . They were all based at Agra in India as part of the 7th (Meeru) Division.

After being ordered to France the 1st Battalion arrived first, disembarking at Marseilles on 12 October 1914, and subsequently took part in the retreat from Mons before fighting the Germans at the River Marne and the Aisne.

After trench warfare set in the 2nd Battalion arrived from India, both Battalions had been mobilised at the start of the war but only the 5th was in action in 1914.

Alexander Wilkie returned home to Scotland in November 1914 having been spared the initial fighting in France. However by March 1915 the 2nd, 4th and 5th Battalions were at Neuve Chapelle and six of the Battalions fought at Festubert in May. In June 1915 he was certified to give instruction in Bayonet Fighting and in September after initial success at Loos, the Black Watch 9th Battalion suffered over seven hundred casualties.

The 2nd Batallion was posted to an expedition in Mesopotamia late in 1915 arriving at Basra on 31 December.

Mesopotamia

A number of European nations, including the British, had, from time to time, had grandiose ideas about building a railway through Mesopotamia and making Asia Minor “the granary of the world” . The German Kaiser however had formed a pact with the Sultan of Turkey and gradually extended German influence throughout the Turkish Empire. The scheme to extend the railway from Baghdad to the Persian Gulf was revived and work began during the 1890s. Britain became concerned at the threat to its domination of the Persian Gulf and the Indian Ocean. The best location for a port at the northern end of the Persian Gulf was in Kuwait, so the Germans started negotiating with the Kuwaitis to purchase land for a port. The Sheik advised the Germans that only one year previously he had entered an agreement with the British Viceroy of India not to sell any land without British consent, in return for British protection. The Germans then pressed the Turks to exercise their sovereignty over Kuwait and annul the agreement. The presence of a British warship in the Kuwaiti port at the time prevented any action being taken by the Turks. After much diplomatic activity the terminus of the railway was set at Basra forty-five miles up the Shat el Arab waterway, in undisputed Turkish territory .

A number of European nations, including the British, had, from time to time, had grandiose ideas about building a railway through Mesopotamia and making Asia Minor “the granary of the world” . The German Kaiser however had formed a pact with the Sultan of Turkey and gradually extended German influence throughout the Turkish Empire. The scheme to extend the railway from Baghdad to the Persian Gulf was revived and work began during the 1890s. Britain became concerned at the threat to its domination of the Persian Gulf and the Indian Ocean. The best location for a port at the northern end of the Persian Gulf was in Kuwait, so the Germans started negotiating with the Kuwaitis to purchase land for a port. The Sheik advised the Germans that only one year previously he had entered an agreement with the British Viceroy of India not to sell any land without British consent, in return for British protection. The Germans then pressed the Turks to exercise their sovereignty over Kuwait and annul the agreement. The presence of a British warship in the Kuwaiti port at the time prevented any action being taken by the Turks. After much diplomatic activity the terminus of the railway was set at Basra forty-five miles up the Shat el Arab waterway, in undisputed Turkish territory . At the outbreak of the war in 1914 a British battalion had advanced towards Baghdad but lack of reinforcements had caused the troops to fall back to the town of Kut, some four hundred kilometres north of the Gulf, on the Tigris River. The town lies in a loop of the river with a small settlement on the opposite bank. In 1915 it was densely-populated with a total of about 7,000 residents. Many of these were evicted as the British army fell back into the town. It had large local supplies of grain due its peacetime role as a marketplace.

At the outbreak of the war in 1914 a British battalion had advanced towards Baghdad but lack of reinforcements had caused the troops to fall back to the town of Kut, some four hundred kilometres north of the Gulf, on the Tigris River. The town lies in a loop of the river with a small settlement on the opposite bank. In 1915 it was densely-populated with a total of about 7,000 residents. Many of these were evicted as the British army fell back into the town. It had large local supplies of grain due its peacetime role as a marketplace.Soon after reaching Kut, the battalion, some thirteen thousand men including over nine thousand Indian troops, commanded by General Townshend, became trapped by Turkish troops and the British sent a rescue expedition under General Gorringe to free them. As part of this operation the 2nd Battalion of the Black Watch was withdrawn from France and ordered to Mesopotamia. The relief expedition turned into a disaster greater than that of Gallipoli.

One of the Black Watch members, Private John Haig, later wrote an account of the expedition to Kut .

We’d been in France wherever the fighting was thickest, right from the start of the war, being sent home from India with the first draft. And we had been in anything that was of any importance - Mons, Ypres, Neuve Chappelle and Festubert. So when they said there was big fighting to do in Arabia, they selected us and we went out there determined to do big things.

We belonged to a big convoy that was going to Salonika, and when it came to the parting of our was we steamed right through the two lines o ships. They gave us rousing cheers that did us g6od to hear, and then we lost sight of them, and heard nothing more till we got to Alexandria, and then they told us a troopship had been lost out of the convoy.

We had understood that we were going to land at Alexandria, and were all ready to do so. Our baggage was on the upper deck of the transport, but when we arrived we got orders to proceed to try to relieve General Townshend at Kut.

Port Said was our next port of call, and here we coaled ship. H.M.S. - with several destroyers and monitors was lying here for the defence of the Suez Canal. They, too, cheered us in a chummy fashion as we cleared the Canal and steamed along on our way. At Aden we stayed long enough to fill all our tanks with water; and at last on Christmas Day we reached the mouth of the Tigris.We had a glorious Christmas dinner: corned beef, with no potatoes and dried biscuits, washed down with a tot of rum. In the evening just about the time folks at home were pulling crackers and sitting round the nice bright fires telling tall stories and enjoying themselves - we humped all our baggage to a second transport, and started off up the river to Basra.

Here the Seaforths disembarked and proceeded in flat-bottomed barges, while we of the Black Watch went on shore to the old Turkish barracks - what a smell they had to be sure! Where we stayed till the last day of the year, when our main battalion arrived in still another transport.

Hogmanay - New Year's Day - which is always a Scotch festival, we’ve kept tip in fine style, singing all the songs we could think of as we plugged along the Tigris in flat-bottomed barges. They hadn't given the main battalion a single day's rest; they'd just chucked 'em from the transport to the barges, and sent 'em along with us up the river.We landed next morning at Kurna, where the Garden of Eden is supposed to be, with a “forbidden fruit" tree as old as Adam and Eve. We didn't get any chance of tasting it, for we were bound for Amara, and after a short spell on the shore we pushed on again. When we reached Amara we did some field work on the sand, just to show that we hadn't forgotten the way to attack.

And didn't it rain! Drops as big as shrapnel bullets fell all around us, and snaked us through and through in less than ten minutes. It was fun seeing us double across that sand, where there wasn't a bit of shelter; and I couldn't help thinking about Neuve Chapelle, where the lead was coming over us every bit as thick as the rain, and the Black Watch advanced through it all as steady as on parade. They didn't mind lead and bullets a bit, but they cursed that rain something shocking!

Back to the barges; up the river in the rain to Allegarbi, where we got out all our gear and prepared to start out the next morning. It was here that I first made the acquaintance of a bed on the sand. It's just about the worst bed you can have. As you lie there, your hip-bone seems to be on concrete, and when you turn over the sand seems to shove out hard ridges, and nearly breaks your back. We got a tot of rum just before we made camp, but there wasn’t a wink of sleep the whole night through for any of us.We were glad when morning came, and the sun shot up in a hurry, as it always does out there. And we were in for a grilling, I can tell you. At eight o'clock we got orders to break camp and start off. I've done some marching in my time out in India and France and at home - but never anything like that. It was hot. It seemed as if the sun had made a bet to scorch us up. There were a lot of new chaps with the Black Watch, lads who'd recently joined and they couldn't stick it. Every now and then one would fall out and rest, done right up with the heat. We were fully loaded - packs, rifles, pouches and bandoliers full of ammunition, water bottles and haversacks full, and our blankets on our shoulders. The very rifle barrels got hot, and if you touched them with your bare hands they raised a blister, while the water in our bottles was lukewarm.

When we halted at four in the afternoon we were just about all out. We lit fires and made tea, but nobody wanted anything to eat; a tot of rum was just about as much as we could manage to dispose of. We simply lay down on the sand and pulled our blankets over our faces to keep the flies off, and as soon as the sun went down and it got a bit cool the rain started coming down again in bucketfuls. But we were too fed up and too tired to move; we simply lay there and soaked through, blankets and all.At seven we crawled out, broke camp, and started off again, and at ten our advance guard came under the enemy's artillery fire. It seemed really funny to hear the guns in this strange land; everything seemed at least a thousand years old and if the enemy had been armed with bows and arrows we shouldn't have been a bit surprised.

There's one thing about the Turks, they're good clean fighters. If they see a man down they won't fire at him, and any wounded who come into their hands they'll bind up and leave for the stretcher parties to find.

We were told that the Turks were retiring, that the Seaforths had got 'em on the run; so we halted again and gave the Seaforths a yell of encouragement, though of course they wore too far away to hear us.

Our colonel was well out in front on his horse, and as we lay there in the broiling sun he came back, his charger all in a lather.

"Fall in, Black Watch,” he yelled out.

"You're wanted up there! There's plenty of work to be done this day - and you're just the boys to do it! "The cheer we gave then simply tore the air. We were all anxious to get a slap at the Turk. We didn't need any coaxing, I can tell you. We were going in support of the Seaforth Highlanders but we got word that the enemy's right flank was retiring, so we spread out in extended order on the left of the line with a whole flank opposing us. We had no supports behind us, and the fire was deadly, and no mistake.

One young lad, just fresh out from home, got a bullet through the ankle, and yelled shockingly. Our corporal, trying to put some heart into him, pulled his leg, and put a bandage round his knee. But the lad couldn’t see the joke. "Where's the nearest dressing-station?' he said, and when we pointed it out to him he started off on his own, limping as fast as he could go. Another bullet caught him and he fell down and the corporal who'd been having a joke with him jumped out of the trench and picked him up. He carried him through the rain of bullets and the hell of shell fire to the station and then came back through it all without a scratch, as cool as you please. We gave him a cheer that meant more than a dozen Victoria Crosses to him.

Just then the Arabs tried to rush round our flank, but the 9th Lancers, a native Indian regiment - met them and gave 'em pepper, red and raw. They beat 'em. back time and time again. It was a glorious sight - the horses crashing against each other, the lances and the swords flashing, and then the white garments of the Arabs streaming out as they flew back on their horses.I'm only telling the cold truth when I say that the ground was dyed crimson. Shrapnel shells and bullets were making the air black; one shell burst in front of me, and I got a smack with a piece of hard earth that knocked me down. Up I got, and was advancing again when a bullet plugged me in the thigh. I got out my field-dressing and tied it up, and tried to crawl on, but my leg seemed to freeze and was a dead weight. So I took off my pack, and used it as head cover for myself.

I lay there a full two hours, till the firing died down and then using my rifle as a walking-stick, started off back to the dressing-station. I reached it at four in the morning, completely exhausted, and when I got there I found over half the battalion there as well. There was nobody to attend to us, and we had to do what we could for each other. It was pitiful, and we cried like school kids who've lost their mothers. Lads were dying off all round like flies and we said some hard things about the hospital people, I can tell you.

The unwounded troops collected us next morning and packed us in the barges and sent us down river, where we were transferred to the hospital ship Varella. We reached Bombay on January 22nd just seventeen months after we’d left India to go to the Front - and I left for Blighty on April 14th.

Private Haig’s account is full of the optimism and patriotism typical of those that were published during the war itself. It only hints at the disaster that had actually taken place.

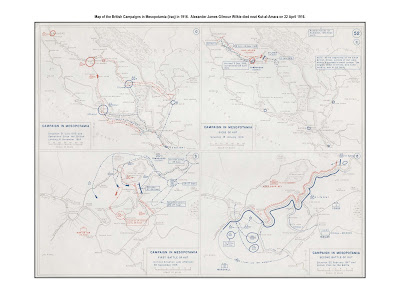

Expedition to Relieve Kut

Many of the men trapped at Kut later wrote accounts of what had happened. One of them, Major E.W.C.Sandes, recalled April 1916 as being:

a month destined ever to be remembered by the unlucky force in Kut, and to be marked in history as a period of desperate fighting by brave troops under General Gorringe. Thousands upon thousands of our gallant soldiers cheerfully laid down their lives before the almost impregnable positions of the Turks in fruitless efforts to save their starving comrades beyond the Es Sin Ridge, and tens of thousands of men and women mourned their loss in England and India, yet glorified their noble end. Forced by the urgency of the situation to deliver frontal assaults across inundated ground against position after position held by stubborn troops supported by good artillery, it is not surprising that their advance failed to reach as far as Kut itself, in spite of superhuman effort backed by highest courage. All honour to the gallant force which so nearly won through the face of incredible obstacles .

Sandes also wrote a day to day account of the rescue attempt in April 1916. The first day of April 1916 was a dreary, rainy day with a gusty south wind. Two hailstorms occurred with hailstones as large as pigeon’s eggs. On the second day of April, the day Alexander's daughter Mary was born in Glasgow, the rain continued and the ground had become muddy and unpleasant. The troops at Kut had reached the stage where they had to kill their horses for food. The Indian troops refused to eat horseflesh and were rapidly losing their strength as each day passed. Some men had hope in the expectation of the rescue force led by General Gorringe.

Before dawn on April 5th, a very heavy bombardment commenced downstream. The detonations of the bursting shells, and the distant roar of guns, shook our houses in Kut and seemed to be absolutely continuous. One could feel the whole atmosphere pulsating with the muffled concussions. This state of affairs lasted until 6:15 a.m. when there seemed to be a lull...it was apparent that General Gorringe must have started on his way and that his troops were even then assaulting the maze of Turkish trenches below Kut.

But the advance of the rescue force was too late. The Tigris had begun to rise rapidly following heavy rains and melting snows in the mountains to the north of Baghdad. The peak flood of the year would be upon the area within days. It usually took about ten days for the flood to reach Kut.

The rescue force assaulted and captured the first five lines of Turkish trenches at what was called the Hannah position.

Throughout April 5th the guns muttered and growled...and the Turkish reserves could be seen grouped in the rear of the Es Sin position [about ten miles downstream to the east of Kut]...at dusk the noise of intermittent firing grew in intensity and finally became an incessant roar. As darkness fell the horizon to the east was a wonderful spectacle; the unceasing explosions of the shells...lit up the distant plains as though a gigantic fireworks display was in progress.

The next two days were relatively quiet and it seemed that the relief force had halted for a rest before advancing further, although the sound of guns could be heard at Sannaiyat, some twenty miles downstream. It was clear that the rescue force would make slow progress. By 7 April the Tigris was continuing to rise and the land for miles around Kut was under water. Both the Turkish and British troops made frantic efforts to prevent the floods destroying their carefully dug trenches.

All was quiet again on 8 April but a tremendous bombardment at Sannaiyat lasting six hours in the early hours of 9 April reinforced the belief that the rescue force was encountering stiff opposition. By 10 April no progress had been made in the advance and the troops trapped at Kut had to reduce their rations to five ounces of horsemeat per day. That would enable the meat supply to last until 21 April if necessary. The Indians still refused to eat horseflesh although the Arabs at Kut had begun to do so. By 11 April supplies of grain for flour ran out.

Fine weather lasted a few days but by 14 April the rains had begun again. Gorringe sent his men forward during the night, knee deep in water, guided by compasses and the flash of lightning. They became lost because their bayonets and the lightning caused the compasses to malfunction . The sky cleared on 16 April and Sandes recorded that “the Turks sat around the dying town like vultures round a dying man, waiting for the end”.

Gorringe tried again the next day. The night lit up again, but this time with artillery fire. The relief force advanced, through their own bombardment and caught the sheltering Turks by surprise, killing most of them. The good news was sent on to General Townshend. It gave some hope to the besieged troops. The relief force was now at Beit Aiessa, about three miles closer to Kut than Sannaiyat. The land between there and Kut was beginning to dry out.

But the victory was hard won and eventually was lost again when the Turks, unable to dislodge the British, breached the banks of the Tigris and flooded the area.

Sandes reported that

Hour after hour the thunder [of guns] went on, till 4 a.m. on April 18th it lessened in volume and finally faded into silence...the Turks had made stupendous efforts to eject out troops from the captured trenches on the right bank near Beit Aiessa. Counter attack after counter attack had been launched, and two of our brigades had at last been forced to withdraw from the captured trenches... It is said that 10,000 Turks attacked our troops in massed formations throughout the night, and delivered on one section of our line twelve separate assaults, each repulsed with awful carnage. The enemy also worked along the trench leading from Sin Abtar Redoubt to the trenches leading off this trench. The slaughter in this trench was great...4,000 Turkish dead were counted at daylight on the bloodstained plain in front of our line...the Relief Force lost about 2,000 men in this desperate combat.

The rescue force could do little more than maintain its position without the help of heavy reinforcements. In the meantime the Turkish forces expanded their defences in front of the British until they took up all of the ground not submerged by the floodwaters of the Tigris.

If General Gorringe's troops were to advance they had to fight both the Turks and attempt to divert the flood to enable their heavy guns to be moved. To this end scores of dams and causeways were built, but this work so tired the men that their ability to fight efficiently became diminished.

The Turks had brought men from Sannaiyat to halt the British advance. Gorrenge decided to launch an attack on Sannaiyat while it was vulnerable and then send the main relief force on to Kut. He had some 6,000 troops available on the Sannaiyat side of the river to attack a reported 8,700 Turkish troops .

Sandes continues.

April 22nd 1916, a disastrous day for our arms in Mesopotamia, saw a desperate struggle in progress at Sannaiyat where General Gorringe was making his last effort for the relief of Kut. The roar of bombardment dimly reached us. The gallant British troops, supported by their comrades from India, hurled themselves against the barbed wire of the Turkish positions, ploughing through seas of mud to get even thus far, and cut down by the cruel fire of dozens of concealed machine guns flanking the entanglements. Over such appalling ground no troops, however brave and determined could hope to win through so strong a defended line held by picked troops equally well armed as themselves.

Our relief force was at length compelled to relinquish the attempt to break through the Sannaiyat position, but not until the ground was strewn with thousands of our brave fellows who had fallen in the attempt. Over the ghastly scene it would be well to draw a veil, were it not for the object lesson conveyed in it of the heroism and discipline of the matchless infantry in our Army. The Relief Force sacrificed itself in a hopeless endeavour for the Honour of England, and failed only after 23,000 men had fallen in the early months of 1916.

This account of the disastrous rescue attempt emphasises the gallantry and heroism of the troops sacrificing their lives “cheerfully” in a futile attempt to rescue their comrades trapped at Kut. As Sandes observes, it was “the Honour of England” which was at stake.

One wonders whether the men really were as cheerful as Sandes suggests, and whether they ever stopped to wonder “Why?”. On the other hand the lot of the soldier, as the immortal lines remind us, was not to reason why, but to do - and die.

Into the valley of death rode the six hundred during the Crimean War. In this battle it was the mud filled trench that was the scene of disaster and it was twenty three thousand who perished, on the British side alone.

Sandes account glosses over some of the realities of the situation. On 22 April at six twenty-five in the morning the Turkish lines came under British bombardment. At seven o’clock two Companies of the Black Watch Battalion climbed out of their trenches and began to cross the 400 yards of mud filled no man's land. They reached the Turkish side before the bombardment had ceased. As a result they were forced to remain lying in the mud without cover until the shelling ended. The Turkish gunners found them easy targets, and they were in a direct line of fire from their own troops at the rear. Once the bombardment ceased those who survived managed to reach the first line of Turkish trenches, but they were so filled with mud that neither Turk nor Highlander could fight in them. The rifles of both sides became clogged by the mud. By the time the next line of trenches was reached, a further twenty yards on, only a few members of the two Companies survived.

Sandes account glosses over some of the realities of the situation. On 22 April at six twenty-five in the morning the Turkish lines came under British bombardment. At seven o’clock two Companies of the Black Watch Battalion climbed out of their trenches and began to cross the 400 yards of mud filled no man's land. They reached the Turkish side before the bombardment had ceased. As a result they were forced to remain lying in the mud without cover until the shelling ended. The Turkish gunners found them easy targets, and they were in a direct line of fire from their own troops at the rear. Once the bombardment ceased those who survived managed to reach the first line of Turkish trenches, but they were so filled with mud that neither Turk nor Highlander could fight in them. The rifles of both sides became clogged by the mud. By the time the next line of trenches was reached, a further twenty yards on, only a few members of the two Companies survived.By seven thirty-five the 21st Brigade began to come to the aid of the remnants of the Highlanders who were by now approaching the third line of Turkish trenches. One of the Brigade's Officers, not realising the plight of the Black Watch troops, ordered a retreat, suffering heavy losses in the process.

The Highland Battalion had used what grenades they had and their guns had mostly been clogged up with the mud. Most of the officers had been killed. The Indian Regiment having responded to the order to retire were in no position to assist, and the 125th Rifles were unable to cross No Man's Land because of heavy machine gun fire. The attack had clearly failed, and the survivors of the Black Watch were forced to retreat to the first waterlogged trenches.

An officer of the Royal Air Force, who had been flying overhead at the time, later reported.

I saw small parties of men on three separate occasions make attempts to get into the Turkish third line down a small nullah. In each case all the men were knocked out and not one came back. To make one attempt was all right, but for men to make two or more, knowing that almost for a certainty their efforts must fail, showed to my mind a bravery, a devotion to duty which must be considered by all who saw it as wonderful .

At eleven twenty the Turkish side brought out a Crescent Hospital flag, the British responded with a Red Cross flag and during the informal truce which followed about 150 wounded British troops were rescued from the mud.

The 2nd Black Watch had only 48 alive out of its original strength of 842 men. The 1st Seaforth Highlanders had 102 out of 962 . Other British units suffered similar losses. The entire three month rescue mission had cost 23,000 lives. Gorringe saw the futility of continuing and ordered a retreat.

On 29 April, after a three month attempt to rescue them, the trapped garrison at Kut was forced to surrender in the face of starvation. The 13,000 men, including over 9,000 Indians, surrendered and were forced to March north to Baghdad. Along the way over 7,000 were to die . The whole expedition to Kut therefore cost over 30,000 lives.

After the fall of Kut a Turkish Officer who had witnessed the rescue attempt said

My men are good in defence, but I have not seen men who will advance repeatedly like yours over open ground under such punishment. Only real devotion to duty will make men do that .

Three years later, on 25 November 1919, a letter was sent from the Infantry Record Office in Perth, Scotland, to Mrs Marjory Wilkie at 38 Aberfoyle Street, Dennistoun, Glasgow. It was a pre-typed form letter with the blanks being filled in. Hardly a personal expression of regret on behalf of the King.

Madam,

It is my painful duty to inform you that no further news having been received relative to 7908 CSM Wilkie A. Royal Highlanders who has been missing since 22 April 1916, the Army Council have been regretfully constrained to conclude that he is dead, and that his death took place on the 22 April 1916 (or since).

I am to express the regret of the Army Council at the soldier’s death in his Country’s service.

I am, Madam,

Your obedient servant,

John Fenton - Captain

Officer in Charge of Records No.1 District

Glasgow

Back in Scotland, at 28 Aberfoyle Street, Dennistoun, Mary Wilkie was just twenty days old when her father was killed. Did he ever know of her birth? News probably would not have reached him in the mud plains of the Tigris. Young Alexander Ernest Wilkie was two and a half years old, and William was close to four.

Marjory Wilkie lost her husband and three brothers during the war and she was left embittered. She apparently did not get along well with Alexander's older brothers and sisters, and after remaining at the Dennistoun address until 1927, decided to emigrate to Australia with her three children.

The career of Alexander James Gilmour Wilkie in the Black Watch Regiment was undoubtedly full of interest, and perhaps excitement, during the years spent in India. One can imaging a great sense of achievement and reward being felt by Alexander as his Battalion formed the Guard of Honour for the King Emperor at Delhi. Pride in the Monarchy and the Empire was significantly greater then than it is today. His chosen career within the army as a Gymnastics Instructor seems to have provided him with interest and rewards as well. But the role of a soldier is ultimately to fight battles. And when the time came to test their loyalty to King and Country on the battlefield the test of the lines “theirs is not to reason why, theirs is but to do and die” perhaps took on a new meaning.

We might, today, speculate upon the futility of the battle in which Alexander Wilkie and thousands of others died. Seventy five years later the town of Kut and the Tigris River were involved in the context of other wars the Gulf War of 1991, and the American led invasion of Iraq in 2003. The battlefield was almost the same, the underlying motives also similar, even though the methods of warfare and technology involved were different in the extreme.

In January 1918 the Black Watch regiments, decimated in number, moved from the Gulf to Palestine – another place that continues to suffer from the colonial and imperial attitudes of the First World War.

Alexander James Gilmour Wilkie embarked upon a career with the Black Watch at the height of loyalty to the British Empire. He died in a futile battle, in a war which many commentators have attributed to rivalry between Empires, to an attempt to defend imperialist expansion and colonial exploitation. That so many should have died for such motives we may see as a tragedy. That so many were willing to make it their career to defend and die for such motives can only say something about their own strength of feeling.

On Saturday 27 January 1923 a War Memorial was unveiled at the John Street Higher Grade School in Bridgeton. It contained the names of one hundred and sixty former students of the school who had died during the Great War. Towards the end of the list are the names of Alexander Wilkie and James Wilkie .

Footnotes

Full documentary referencing of sources is available for this information. Contact me for details.

No comments:

Post a Comment